Let's talk about money

Any gamblers here? Playing cards are money. Well, they were. Seriously. Having grown up in Canada, I learned about a very interesting kind of money that not many people have heard of - playing cards! Before Canada became a country in its own right in 1867, it was comprised of two colonies: British North America and New France. Settlers from Europe started moving there during the 1500s, and in 1608 Samuel de Champlain established the first colonial settlement of New France on the St Lawrence River, at a place that today is known as Quebec City.

To support the economic development of its new colony, money was sent over on ships from France. Both paper money and coins were used, but interestingly, because it was more difficult to transport coins due to their weight and bulk, in New France coins were attributed a greater value than notes.

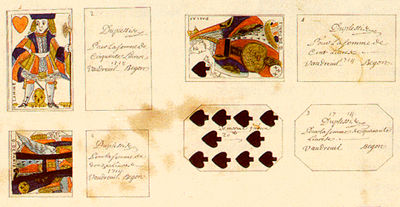

In 1685, the colonial government faced a crisis. New France had waged a failed war against the Iroquois, an aboriginal tribe who were allied with the British. Tax revenues had fallen because of the war, due to the fact that trade volume had dried up as the merchants were conscripted into the army. But the soldiers had to be paid. A local official named Jacques de Meulles had one of those “lightbulb” moments. He would use playing cards as money!

The first issue of playing card money was on 8 June 1685, and it was redeemed by the authorities for French money three months later. Writing to the Minister of the Marine in France, de Meulles explained what he had done:

“It occurred to me to issue, instead of money, notes on cards, which I have cut in quarters . . . I have issued an ordinance by which I have obliged all the inhabitants to receive this money in payments, and to give it circulation, at the same time pledging myself, in my own name, to redeem the said notes.”

Playing card money was used again in 1690 and, despite the offer of redemption for French currency, people chose not to redeem their cards and continued using them as money. It was fraught with problems, particularly counterfeiting, but continued to be accepted by the local population until 1717, when the French government redeemed all remaining playing cards at 50% of face value and permanently withdrew them from circulation.

It’s fascinating to think of using playing cards as money, but it worked. Under economic theory, there are three tests to determine whether something qualifies as money. It must be:

- a medium of exchange – something that can be passed from one person to the next, and is accepted by both parties to a transaction;

- a unit of measure – the amount it represents must be clear and agreed by both parties;

- a store of nominal value – if you choose to keep money instead of spending it, the value must remain. Note that I say nominal value, for inflation is a very real thing, but more on that in a future post.

As long as the people continued to accept it met those three tests, playing cards were money.

Until next time…